‘[D]o you not realise that the State is the worst enemy you have? It is a machine that crushes you in order to sustain the ruling class, your masters. Like naïve children you put your trust in your political leaders. You make it possible for them to creep into your confidence, only to have them betray you to the first bidder. But even where there is no direct betrayal, the labour politicians make common cause with your enemies to keep you [on a] leash, to prevent your direct action. The State is the pillar of capitalism, and it is ridiculous to expect any redress from it.’

– Emma Goldman (1893)

On Friday morning, upon opening my phone, I encountered an article from EdinburghLive’s online news service regarding one man’s solo protest outside Saughton Prison. Entitled ‘Wheelchair bound ex-prisoner stages one man protest outside Saughton Prison’. Alasdair Clark’s article advised that ‘[a]n ex-prisoner [identified as Robert Danilczuk] has been staging a one man protest outside HMP Edinburgh’ since late July 2020.

Whilst Clark’s report quoted several local residents – one of them suggesting that Robert ‘had been jailed for possession marijuana’ – it struck me that the reporter may not have spoken to Robert directly. Rather, it was stated secondhand that Robert ‘claimed to have been left disabled after being beaten in the jail’, noting his ‘protest banners with claims against the prison written on them’. The absence of direct conversation with Robert was further confounded when the same resident interviewed earlier in the piece told Clark that ‘he didn’t not [sic] think Robert was there to “beg”, [but] rather to ask for his basic human rights’. After contacting the friend who’d posted the link to EdinburghLive on her Facebook account and being told she’d taken him a pillow to help make Robert more comfortable in his tent, I wanted to offer similar support and hopped the 38 bus towards Saughton with my dog, bell, in search of him, armed with a bundle containing winter socks, a blanket, wet wipes, and bottled water.

When I arrived outside the prison, Robert was sat on the ground, reassembling the base of his wheelchair with the assistance of a tall lad who was nipping back and forth to his van. With Robert’s permission, I joined him on the ground, situating myself beside his tent, chatting with the two as they worked on the chair. It turned out that the lad (an activist with an Edinburgh-based anti fascist movement) had fully charged both of the chair’s batteries – a task he advised normally takes close to eight hours. Similar to myself, the lad (‘S.’), had heard of Robert’s situation through a friend and we quickly discovered several mutual pals within the trade union and activist movements in the Scottish capital and a further mutual friend in an activist-author down south in England. It turns out Robert’s so adept at rebuilding his chair, in part, due to his time as an engineer.

As S. headed to buy a few large bottles of water from ASDA, I introduced myself properly to Robert and bell quickly took to him. I explained how I’d heard of his protest, and he immediately remembered my pal who’d brought him a pillow earlier in the week. I explained about the type of work I do with the Community Hub / Foodbank Partnership in Tollcross (central Edinburgh), explaining that if, after the protest ends, he wants any assistance with pursuing his housing options, welfare advice, or to access our clothes bank, he will be more than welcome to join us there. We talked through the bundle I’d brought with me, and Robert accepted the wipes, socks, and water, though he explained he was well stocked for blankets and the book I offered him wasn’t something he could use due to poor eyesight.

I told Robert about the EdinburghLive article and asked if he wanted to talk about his situation as the article had been absent of any input from him. After explaining that many folk had taken photos of his protest, offered him food (which prior to his current hunger strike, he’d readily accepted), and spoke of others who had taken the time (like I intended to do) to offer our support from our professional services in relation to housing, social security, etc. The two of us spent a few hours chatting in the spittering rain and after advising on the help I could offer through my works, Robert said he was keen on me utilising the platforms I have (e.g. through Lumpen, Left Ungagged, and Bella Caledonia) for a write-up about his actions and experience with authorities here, in Poland, and in Cyprus. I therefore hope that this account does justice to that request. I also want to add that I understand from Robert that two others may be producing reports on his experience soon, so I want to stress that this article is intended to (at Robert’s request) draw attention to his protest rather than to step on anyone else’s toes and whatever plans they may have.

Throughout our chat, Robert sits peacefully, a smile on his face as he laughs and theatrically shares his story with me. With his permission, I chainsmoke, sat a metre or so away from him. My dog, bell, is fast asleep (at first in my lap; then in his). Robert outlines his experiences and reasons for the protest, being incredibly open about his own life and given the connections we have between those I know in my personal and activist lives who have helped him, there’s a seeming mutual trust (or at least a sincerity) formed early on. He shows me his fake teeth and tells me he lost all bar five or six of them during his short time in Saughton. He kisses and plays with bell as we discuss his hunger protest which he’s just two days into after feeling little was achieved during the first three weeks of his static protest.

He tells me he’s a family man, with two ex-wives and seven children (one adopted following the death of a close friend). He’s very kind to bell as she jumps all over him and explores his wee tent. Prior to his time in prison, Robert always kept dogs and he shows me a photo of his pitbull. Most of his family are currently based in and around the Barrowlands in Glasgow now, with him having moved there from Bydgoszcz (Poland) after a stint running his own building company in Cyprus. He’s well travelled, well educated, and an avid chess enthusiast. At one stage, Robert spoke six languages, though he says the memory issues he’s experienced since the incident in Saughton have left him feeling he can only communicate in Polish, English, and Russian now. Greek and Italian, however, are gone. He doesn’t mention the sixth.

He’s incredibly honest about run-ins with the authorities whilst growing up in Poland before he began channeling that youthful restlessness into sport, leading us to a brief chat about the British and European boxing scenes. A minor familial issue in Poland led to a criminal record and this, he advises, is why the EdinburghLive report suggests he was ‘jailed for possession marijuana’ (see Clark’s aforementioned article). Despite having already lived in Scotland for several years, finding work in a local butcher’s, he tells me that it was accusations from his time back in Cyprus that led to the police coming to his door in Glasgow. Whilst being held in prison, Robert says he was mistreated by men in black uniforms and that he became concussed after being forced onto the floor. When he awoke in the hospital, his speech was slurred and he couldn’t move his legs.

Whilst in hospital and briefly when being supported by care professionals, Robert tells me he developed very positive relationships with some staff, describing them as ‘family to me’. Even as he turns, pointing at the prison entrance, he says that there are ‘many good guys in here; though many bad guys also’. When he was extradited to serve his seven year sentence back in Poland, he encountered many frustrations with missing paperwork leading to inadequate facilitates and inappropriate housing in the Polish prison – nothing adequate for a wheelchair-bound prisoner. It’s at this point we discuss the distinctions between the U.K. and the Polish prison systems, in particular, he suggests that whilst in the Western European states many prisoners are released early for good behaviour, in his experience, it’s more likely that additional years will be added to a sentence in the east rather than any kind of reduction. Several appeals have been lodged by Robert and various teams of lawyers over abuses of human rights, though these situations are still ongoing but he tells me these have been escalated to the European Court of Human Rights (Cour européenne des droits de l’homme) in Strasbourg (France).

Robert’s sentence ended in 2018 and he immediately returned to his home in Glasgow. Yet, despite his physical disabilities, Robert advises that a D.W.P. Assessment left him with zero points and therein no state support. He’s very kind in his reflections on the situation his first family endured when he faced prison back in Poland many years ago, detailing the dire circumstances families are left in due to the lack of state support for anyone with an incarcerated parent. A step-father to his children was thus an important step in safeguarding them in his absence. With a significant period of time spent in hospital as well as prison, Robert tells me that social workers in Scotland were eager to help house him, yet it wasn’t until after repeated offers were knocked back due to his poor condition requiring hospitalisation that he accepted a third offer of accommodation for fear he would no longer be offered somewhere due to a perceived lack of engagement by these state actors.

There have been many amazing people helping him out over the last few weeks, bringing him pillows, blankets, food (prior to his hunger strike commencing), and charging the batteries for his wheelchair. Whilst we sat chatting, several others voiced their support in passing and shared familial experiences of the prison system – three (slightly…) tipsy teens walking by said they admire the stance he’s taking. Robert showed the lassies the scars on his arms and they waved back as they crossed the street. There’s a comical moment as Robert asks me to clarify what the young women shouted. A significant number of Lothian bus drivers now know where he’s based on their route and some (though certainly not all) are taking care to avoid splashing him, his tent, and the chair. He tells me of other Polish residents who’ve offered to help get a roof over his head, and that others from Turkey, Greece, and Pakistan have offered food and money.

As someone with circa twelve years of experience in community-based practice (adult education, youth work, queer and broader social inclusion, anti-racist education, and youth homelessness), direct and mutual aid is something I hope to better enact going forward. The aforementioned Community Hub (something I’ve written about previously for Lumpen: A Journal of Poor and Working Class Writing) is the more service user-led action I’ve been involved with, yet there remains the distinction of service user – practitioner relationships rather than peer support. To this end, I’ve watched closely and supported folk as many support groups have emerged during the current pandemic; whilst I also want to express my admiration for Edinburgh Mutual Aid and Mutual Aid Trans Edinburgh (M.A.T.E.). If you’re in a position to, please support these or similar community-led, locally-organised groups in your area.

It’s in this ethos of enacting mutual aid rather than necessarily donor-based charity that I attempted to crowdsource the materials Robert said would be of use to him – the boots and a cover for his chair. Several folk shared the post, and there were kind words in a handful of community share groups across Edinburgh – though one of those groups with several thousand folk removed the post with an admin messaging me ‘[s]orry but this is not an information / campaign page’. Whilst other groups (including the wonderfully supportive Edinburgh Queer group) encouraged members to do whatever they could, admins in this particular share group distanced themselves from my post, stressing that they wanted to keep the group ‘only asking for and giving away things / skills in the [specifically named] area’. A disappointing stance in space intended for cross-community support. It links directly to a comment Robert made during our chat:

‘These people who fighting on me and the others [sic], and these people who see and are doing nothing – it’s the same guilty [sic]. It sends, for me, a bad message’.

There were several emotive comments from friends who shared the post for me with links made to the panic buying some folk were able to do at the start of the pandemic. One comment stating ‘a pair of old boots, can we take a minute to think why another human is actually asking for that? How utterly horrific […]. Six months ago people were fighting for toilet roll and pasta in Sainsbury’s! sadly a lot of people didn’t […] have that luxury’. One recently retired friend reached out to me, transferring £55 to purchase a new pair of waterproof boots for Robert. A sincere and massive thank you to each of them. When we chatted, Robert showed me a metal flask that had earlier contained hot lemon tea (the only kind he’ll drink) that someone had brought during a repeat visit. Another person has dropped me a line to offer a large fishing poncho that may help cover the electric wheelchair. Some folk had materials, others had money, or time, or public facing platforms. The point is that mutual aid is about providing what we can to each other based on the means we have at our disposal.

Robert’s protest is not abolitionist in nature, rather he’s demanding accountability. His articulation of the functionality and mechanism of the prison system in Scotland and Poland is nuanced, with insider perspectives that demonstrate the unique interpersonal relationships between prisoners and staff in these divergent contexts. It’s a demand for justice that he articulates in a manner not too dissimilar to the tactics deployed by the recently deceased Stuart Christie when, allied to the likes of Albert Isidore Meltzer and Miguel García García, the Anarchist Black Cross lobbied the Spanish authorities to adhere to their own legislation promising humane treatment of prisoners. Many of us on the Scottish and international political left are, of course, once again returning to Christie’s works following his death. Certainly Robert’s intentions sound closer to this than a desire to become part of the abolitionist movements advocated by the co-founders of Critical Resistance, Angela Y. Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, for example.

When we talk through what justice would look like and what would constitute success for his protest, he tells me that he wants acknowledgement that there is a problem with how staff treat prisoners in Saughton. He tells me this protest is not merely for him but for others he may never meet but with whom he shares experiences of institutional abuses or failures. When I ask him if he knows whether the people he attributes his disabilities to still work there, he says that it doesn’t matter about the individuals – this is about institutions and power. Given his own health struggles and issues with diabetes, he acknowledges that it’s likely he’ll end up back in the hospital, but he is fully committed to his cause. As his sign says:

‘I am not here to beg. I stand here to die in protest. Let the world know. Grant me my rights or give me back my health!!’

As the rain gets heavier! I help wrap his wheelchair in bin liners to protect the battery. We say ‘dobranoc’, and I tell him that I’ll be back once I can source the materials he requested. With thanks to members of the Edinburgh left community, I’m headed back there now.

______________________________________________________

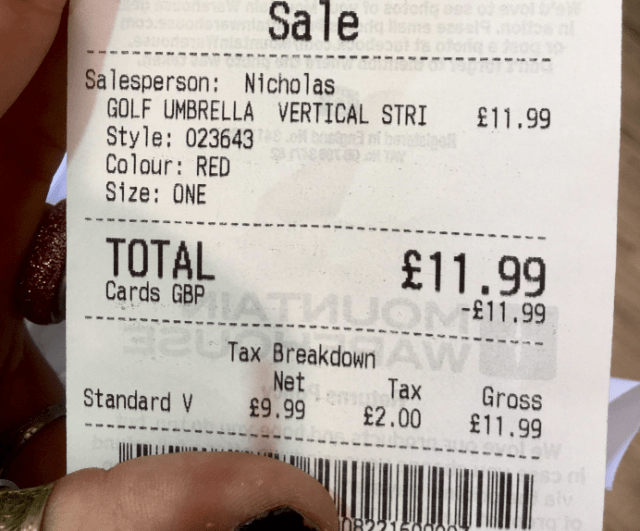

For full accountability on my part, I include a photo of the reduced boots purchased for Robert (£99.99 down to £39.99) and a copy of the receipt detailing the waterproofing spray to help reinforce his tent (£7.99), a boot spray to keep his boots in good nick (£5.99), and (in the absence of any waterproof sheets from the six shops I tried in town) the large umbrella (£24.99 down to £11.99). These items were purchased in the summer sales in Edinburgh city centre whilst observing social distancing measures.