As someone who was not as academically gifted, I was lucky enough to have parents who are both creatives in their own ways, who capitalised my creative successes and pushed me towards what I was naturally more drawn to. I then ironically in a state of teenage middle-class angst rebelled against art in the most middle-class way possible by making my way to a Russell group university to study Politics and Criminology – not exactly sacrificing all the efforts my parents had made for me. However, I was afforded that choice – which is not one everyone has access to.

There exists within art a unique dichotomy – that of the value we afford it and the lack of value to those who create it. The global art market which is worth 65.1 billion dollars, and consists of cultural reference points throughout history: Van Gogh, Rembrandt, Warhol, Da Vinci, Michaelangelo. These household names and art movements which have shaped not only the world we exist in from architecture, to what we wear, have been given and rightly so – statue and regality. There has always been something mystical and intangible about the art world. It goes beyond physical commodities and is more than just a skill but a way of thinking – to be creative is to interact with the world through fantasy and emotionally, there is no limitation, no impossibility within imagination.

To me to be imaginative, to be creative is to be free, it is to see the world as ever changing – there is nothing solid or definable. And whilst the future is never certain, it feels as if we are now living in a new-found state of insecurity and uncertainty – socially, politically and environmentally. There has never been a time where being creative could be someone’s largest asset, but who actually has access to being creative?

We treat creativity as a luxury, as a pleasure which only some can access. We saw the defunding of the arts post 2008 financial crash and it has never fully recovered, with further more aggressive cuts of up to 50% in higher education in 2021 whilst STEM rose by 12%. These cuts, just as all financial decisions are, are a statement – one which reflects what the government values. The message also sets a precedent nationally as to what is valuable, what is successful – the constant reinforcement and funding of STEM over the arts, undervalues the skill and worth of creatives: post-covid the government ‘retraining’ campaign again targeted creative industries, emphasizing again its narrative of disinterest and lack of commitment to the importance of the creative industry.

A recent article ‘Are art degrees becoming just for the rich’ it discusses Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural reproduction in which people want to improve their social standing, going into the arts and investing time into them, is not be seen as an investment but as something that people who can afford to can go into.

The courses that are cut to meet the implications of limited finances are often those areas of learning that are underpinned by creativity, adaptability and boundaryless thinking. The kind of skills our unknown future will require. We have an education system which was built to fit industrialism and is educating children for a world we don’t know what will look like, shaped by the world as it was, not for the future.

Ken Robinson in his TED TALK articulates the concept of ‘educating out of capacities’ – where we have been taught that to be wrong is to fail, we are being stripped and mined for a particular commodity and the cost of this is creativity: if you are not prepared to be wrong you’ll never come up with anything original.

The continuous pattern to only acknowledge a certain type of ‘academia’ as ‘clever’ underlies the continuous struggle associated with art and also undermines it and this tension serves no one, least of all lower-class creatives.I am lucky enough to know many creative people – my dad being one of them. His creativeness is evident in every element of his life, however he has always felt robbed of his potential due to his impoverished childhood which left him with a disadvantage.

He had little access to the arts and was discouraged from pursuing anything creative. This means that he has always struggled to harness his creativity in a way that he wouldn’t have if he had have grown up with more financial security and more support at school.

The defunding of the arts not only represents what is and isn’t valuable from the powerful, it also turns art ‘classist.’ It creates it into something that is not a free choice, but something that not everyone has the luxury of. To continue in whatever form in higher education to do a creative subject, you need to have financial aid and whilst there are schemes and bursaries available for some students its more than just financing of a course, there is a very legitimate risk involved – the instability of the creative industry employment is one which negates a lot of people from committing, because it doesn’t usually offer guarantee of employment nor financial stability.

If not studied in school, it is highly unlikely to have access to studying later in life – only 12.4% of film, tv and radio is made up of people from lower class roots. And with low value in state education given to the arts, and the high cost of undertaking arts in higher education lower class background less likely to undertake an arts degree. And further perpetuates the idea that the arts are reserved for those in higher classes.

Access to the arts is not only confined to education but expands across all avenues of life from: cinema tickets, owning a camera, art galleries, festivals, books – all the things that a lot of people consider normal and accessible. If there is never a space or money to be exposed to the arts then lower-class people will forever be less likely to become creatives, and it will continue to predominantly be the middle and upper classes who produce and consume art.

The isolation from possibility: creativity, is impoverishing beyond just culturally, but also developmentally. It takes away the freedom to think and experience life without boundaries, it is escapism in its most beautiful form.

For me having access to the arts, to have space to be creative in whichever way you experience it, should be a given, we should be promoting, pushing and applauding it. It is the future – but a future which should be accessible and promoted to all, not just those who can afford it.

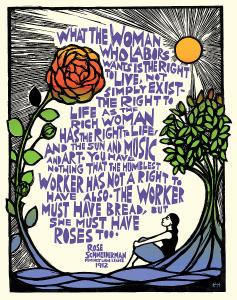

Featured Image is “What She Wants” by Ricardo Levins Morales

Available to buy as poster, here.